The guttural throb of two powerful engines rattles the cramped cabin of our chartered Twin Otter aircraft, piled high with paddling gear. Nine eager passengers crane their necks to scan the arctic waters for beluga and right whales.

We have flown from Edmonton, Alberta,to Inuvik, NWT, where the stunted northern treeline meets the historic Mackenzie River. From Inuvik we chartered the Twin Otter to take us north, two hours and 750 kilometres across the Beaufort Sea to Banks Island, the westernmost of Canada’s High Arctic islands. A two-week paddle will take us down the country’s northernmost navigable river, located in one of the nation’s newest and least-visited national parks—Aulavik.

We are an eclectic mix of arctic buffs, sea kayaking enthusiasts and birders drawn together by a shared urge to explore Canada’s mystical High Arctic regions. Our ages are as diverse as our interests, ranging from the cherubic seven-year-old Navarana Smith and her stuffed animal entourage, to the ageless Nipper Guest. Nipper’s tales of his far-reaching global adventures—everything from the horror and glory of WWII to riding his bike across Canada at the age of 70—will fill our windbound days with smiles and respect. Falling somewhere in-between on the age scale, the rest of us try our darndest to match the boundless energy of these two exuberant arctiphiles.

Our final brush with civilization is a brief stop to refuel and pick up supplies in Sachs Harbour, a community of 150 on the southern tip of Banks Island. Fully supplied, we zoom north across endlessly rolling tundra, flying low enough to see small groups of Peary caribou, flocks of snow geese, packs of wolves and herds of muskox panicking from the roar of the aircraft.

Dominating a broad, fertile valley on the northeastern tip of Banks Island is the azure meander of our destination, the Thomsen River, snaking its way through ancient glacial till toward the Arctic Ocean.

The plane leaves us and our mountain of gear on a small gravel bar near the river, in the middle of what the Parks Canada website calls “one of the most remote places in North America.” A charter

flight from Inuvik costs over $20,000, and the park gets an average of 25to 30 visitors a year.The only signs of modernity in the park are two tiny shacks of wind-free comfort in 12,000 square kilometres of untouched arctic landscape.With more than one muskox per square kilometre, the land is an arctic Serengeti, one of the world’s great remaining intact wilderness areas.

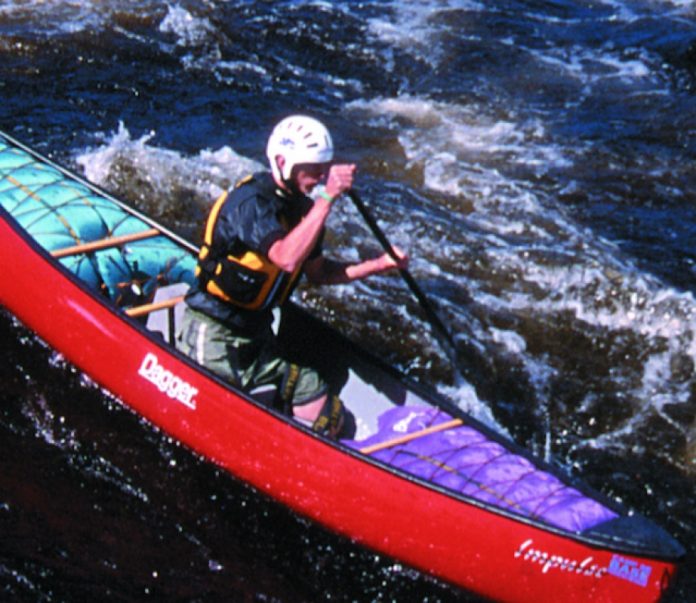

At midnight, the sun is still high in the northern sky, casting the warm light that photographers live for. We eat a 2 a.m. dinner in a persistent north wind and begin to set up our folding Klepper kayaks as two yellow-billed loons eye us suspiciously from the river. These boats give us the freedom to paddle in remote airdrop-only regions. Folded, they occupy two large suitcase-sized bags that will fly anywhere. Set up, they weigh in at 70 pounds and will hold enough gear for months of well-planned exploring. Their wood frames and canvas/hyperlon skins mimic the designs that originated in the arctic regions a thousand years ago.The kayak provides a per- fect conduit for historical exploration of these regions.There is no more effective time machine than a historically relevant means of travel and an active imagination.

On Banks Island, wind seems to constantly stimulate the senses, keeping the notorious arctic insect hordes grounded at the same time. The clouds of mosquitoes do not seem as intent on biting as on simply irritating all living things.

For two weeks, the current of the Thomsen carries us steadily northward and we are boggled by the abundance of life on Banks Island. It brazenly contradicts our mental image of “the barrens.”

A snowy owl twists its tail and wheels from its arcing glide, its sharp eyes drawn by a ripple of movement across the tundra below. The owl feeds on the abundant lemmings, ptarmigan, and small birds. Each brief arctic summer, snowy owls fly 3,000 kilometres north to breed in the Thomsen River valley, where they are joined by over 50 other species of migratory birds.A short stroll among the endless tundra ponds dotting the landscape would fulfil any North American birder’s wildest dreams.

The treeless landscape leaves wildlife almost naked—a wolf cruising along a ridge a kilometre away will catch the eye like a lightning bolt in a cloudy sky.The dark shapes of muskox grazing in a sedge meadow stand out like boulders on a snowfield.

Biologists trace only one living relative to the muskox—the takin of the Tibetan high plains—and these two isolants rest somewhere on the evolutionary line between goats and antelope. Seventy thousand muskox roam the valleys and swails of Banks Island. These staggering numbers are testament to the astonishing capability of the Western Arctic’s vegetation to support life and provide locals with a valuable source of revenue and food.

As we float down the river,mysterious white forms,out of place in the low sea of brown-green tundra vegetation, catch our eyes. We rudder hard and cross the steady current to land our kayaks on the far shore below the strangely white-speckled hill. We stumble like drunks over the endless tundra hummocks, trying in vain not to disturb the fragile blanket of flowers. A pair of croaking sandhill cranes soars noisily overhead, and a small flock of Lapland longspurs flits nervously from our path as we reach the first of the weather-bleached objects.

The objects turn out to be ancient bones, some bleached, others painted with the brilliant orange of xanthoria lichen. Small bits of caribou antler, ribs, vertebrae, and scapulae are spread over many hectares of this lonely, wind-blasted hillside. But the muskox skulls are what really trigger our primordial imaginations. Someone bends down to inspect a bone—the teeth of a primitive saw have scarred it. With no reminders of modernity to anchor us in the present, no sign of today’s culture anywhere to be seen, our thoughts travel 500 years back in time.We imagine the peaceful serenity shattered by the baying of the dogs that walked with the Inuit.We can almost see the dogs as they drive the muskox to the top of the rise, where the herd predictably forms a defensive ring, young near the center. Their shedding winter underfur, called qiviut, waves in the arctic wind like ragged flags flying from the animals’ humped forms.

This instinctual defence works well against the muskox’s main predator, the arctic wolf, but is suicidal when the attackers are armed with arrows and spears. Soon the animals are killed and butchered. Extra meat is buried under heavy stones to keep the foxes, weasels and wolves away until it can be used. What we see today are these grave-like meat caches along with the stone tent rings of the hunters’ families.

The gradual evolution of cultures in this region took a sudden leap in 1851 with the arrival of the first Europeans.The great age of arctic exploration was in full swing, and dozens of European ships cruised the ice-choked waters in search of the grail of that age—the fabled Northwest Passage to the rich lands of the Orient. Ships and men were marooned and starving all over the Arctic. It was only a matter of time before one of the poorly prepared European expeditions came ashore on Banks Island.

Captain Robert McClure led one of a wave of voyages sent by the British Navy to determine the fate of the now-infamous Franklin expedition. McClure sailed the HMS Investigator from Hawaii around Alaska to the northern tip of Banks Island, inching his way eastward until he encountered heavy ice in September, 1851. McClure sought a safe haven from the impending arctic winter in a small harbour near the Thomsen River delta, christening it, with pre- mature optimism, the Bay of God’s Mercy. It was the last harbour Investigator would ever enter.

The following summer came and went with no sign of the Investigator’s icy trap melting. The expedition was forced to spend a second winter in total darkness. Supplies and crew morale disap- peared along with the sun.

Finally, a rescue party from the Investigator’s sister ship, HMS Resolute, spotted two members of McClure’s crew who had been sent in search of help.The two lonely figures, blackened from head to foot with coal smoke, were wandering the ice near Banks Island. McClure and his crew abandoned the Investigator and returned to England, becoming the first Europeans to complete the Northwest Passage.

The precise fate of the 450-tonne, copper-sheathed ship is not known. All that remains of the ship are some old piles of coal and a few barrel staves.The more enduring stone and bone signatures of the Copper Inuit tell the rest of the Investigator’s tale. Archeologists know that sometime in the mid–late 19th century, the Copper Inuit abruptly changed their migration routes to use the Thomsen drainage as a main travel corridor.

The Investigator’s wreckage may have prompted the shift. One can only think of a wrecked spacecraft, full of unimaginable technologies, to get a hint of the significance of this discovery to a people whose only sources of wood were the occasional piece of driftwood and tiny bits of arctic willow. Early translations of Inuit encounters with similar ships indicate they believed them to be carved from a single block of wood! In addition, the ship’s copper, iron, and woven fabrics would have been a lottery-sized bounty. In Mercy Bay, the visible remains of over 150 campsites and 3,000 muskox skeletons are the legacy of annual trips to gather goods for everyday use and for trade.

The ponderous tale of Banks’ 4,000-year human history culminates in Sachs Harbour where the formerly transient Copper Inuit that once came off the ice in the warm arctic summers to follow the muskox and caribou are now permanently anchored. Here, the centuries-old practice of muskox hunting continues, but in a highly modernized form.

The Inuit use ATVs and Skidoos to round up the 3,000 muskox to fill their quota. The animals are herded from holding pen to holding pen, bringing them eventually to a large pen near the village. Here the animals are processed—the meat shipped out in 30 DC-3 loads to Edmonton for packing, and the qiviut shipped to Peru to be carded and spun.

This mystical fibre is purported to be 10 times warmer than wool by weight, and has the silky texture of cashmere. Stores like the Qiviuk Boutique in Banff sell qiviut sweaters to high-end tourists for as much as $5,000. Back in Sachs harbour, a dark stain of entrails on the ice in front of the village, waiting for the spring melt, is all that remains of the yearly muskox hunt.

An estimated 18,000 muskox reside in the Thomsen River valley, and we continually paddle past small herds of these Paleolithic beasts. Typically, our five boats drift toward a resting group of muskox until one exceptionally vigilant animal slowly rises to inspect us.

One by one, each animal in the herd stands, looks at us, and glances at the others as if to say,“are we really seeing what I think we’re seeing, and should we be worried?” Finally, one animal decides that, yes, they should be worried, and its break from the riverside sends the entire herd stampeding wildly across the tundra.

But we did not arrive by dogteam like the hunters in the animals’ ancient memories. Nor are we clad in the furs of the Old Ones, but in colourful modern jackets and pants, with toques permanently affixed to our crowns to ward off the seeking north wind.

And it’s not the sound of barking dogs that spooks the herd, but the drone of an approaching plane. It circles the gravel bar once, twice, then puts down with a dusty roar on the makeshift airstrip. We pile into the belly of the plane, take off with a roar and speed steadily southward, forward to the 21st century.

Dave Quinn of Canmore, Alberta, teaches high school outdoor education and guides kayak trips in the Canadian Arctic, the Queen Charlotte Islands and Patagonia.

This article first appeared in the Winter 2002 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Winter 2002 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Winter 2002 issue of Rapid magazine. For more great boat reviews, subscribe to Rapid’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Winter 2002 issue of Rapid magazine. For more great boat reviews, subscribe to Rapid’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Fall 2002 issue of Rapid Magazine.

This article first appeared in the Fall 2002 issue of Rapid Magazine.

This article first appeared in the Fall 2006 issue of Rapid Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Rapid’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Fall 2006 issue of Rapid Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Rapid’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Fall 2002 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Fall 2002 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions