In the fall of 2008, I traveled solo to Nepal. I brought only my boat, my camera and a vague idea of the whitewater potential of a small country with the Himalayan Mountains as its backbone, but I was hopeful that would be enough. Nepal has everything you could want for whitewater kayaking: plenty of gradient, post-monsoon high water, and a mountain-dwelling populace intent on keeping adventurous visitors fed and comfortable.

Himalayan Hijinks: Whitewater kayaking in Nepal

I arrived just as the last monsoon clouds were clearing and managed to join a raft-supported trip on the high volume, low elevation Sun Kosi. Led by Dave Allardice, a new Zealander who pioneered whitewater rafting in Nepal, the trip celebrated 20 years of successful rafting in the Himalaya and reunited many of the first generation guides for one more run on this 300-kilometer, multiday beauty. The Sun Kosi trip also connected me with two keen and hilarious American boaters, Mefford Williams and Shawn Robertson, who became partners for ensuing paddling missions.

Meet you in Kathmandu

In Kathmandu, the frenetic capital of Nepal, Williams, Robertson and I regrouped at the Hotel Holy Lodge to organize transportation and figure out logistics for some higher elevation assaults. Walking into the Holy Lodge, a known kayakers’ hangout in the tourist ghetto of Thamel, we were surprised to see some familiar faces.

JJ Shepherd of South Carolina, a veteran of Himalayan kayaking missions, had just rolled in from a rafting trip and Norwegian huckster Benji Hjort was on a quick sabbatical from his teaching job. Seconds later, a distinctive voice announced the presence of Kiwi talent and young punk Sam Sutton as he emerged from his room with his usual larger-than-life charisma.

You have to love Nepal’s whitewater kayaking community

You show up alone in a distant country and somehow find a solid team of old and new friends just in time for the first big mission. But what was that mission going to be? Shepherd directed our focus on the Modi Khola, a river flowing right out of the spectacular Annapurna Sanctuary.

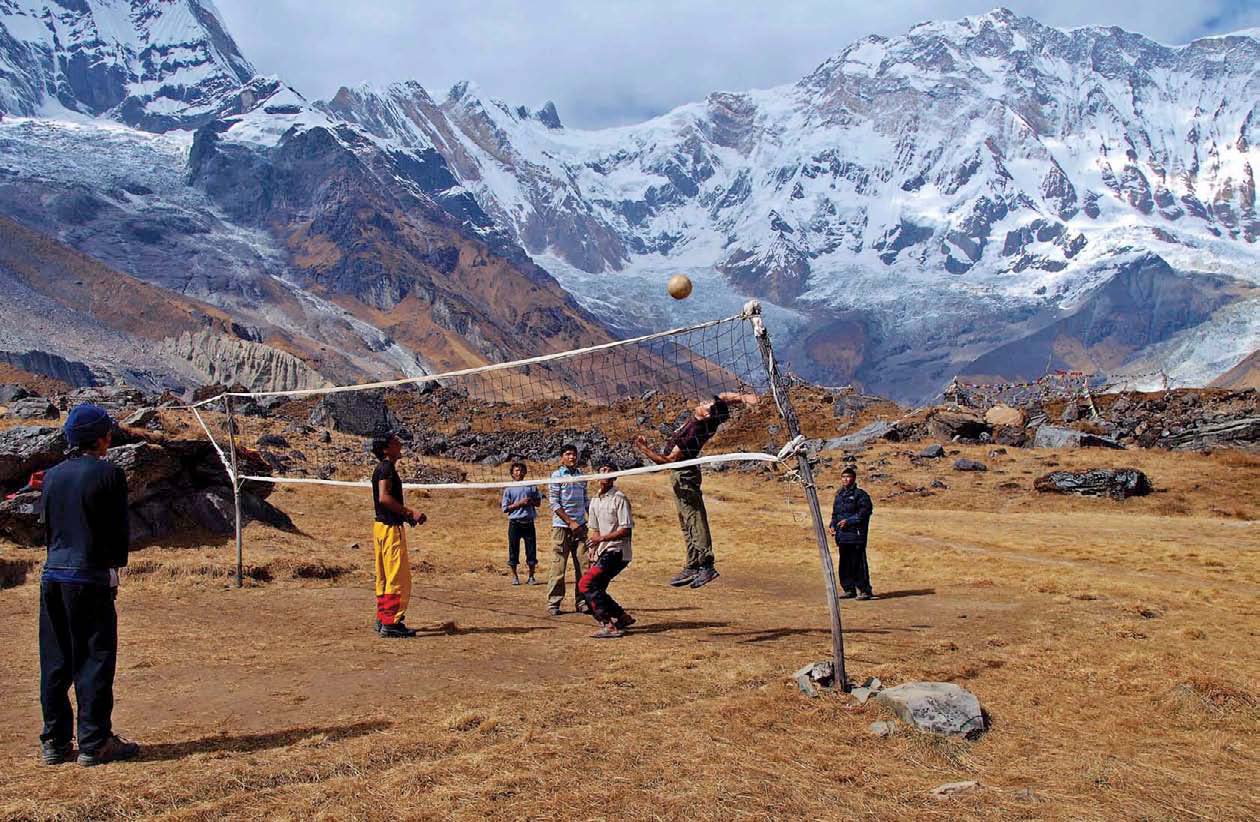

We endured the six-hour bus ride to the Annapurna Conservation area from atop the rickety Tata’s roof, hanging on for dear life and ducking overhead power wires. The strenuous, one-and-a-half-day hike from the Annapurna Sanctuary trailhead up the Modi Khola valley rewarded us with one of the most spectacular river put-ins in the world.

Annapurna South and Machapuchare peaks loomed nearly six vertical kilometers above the steep mountain creek. A total of eight 7,000-plus-meter summits in the surrounding Annapurna Massif, including 8,091-meter Annapurna One, fed the Modi Khola.

A few initial kilometers of wonderfully continuous class IV soon evolved into stomping class V rapids as the creek gained volume and inertia. After a long day on the river, we walked to a nearby village for a dinner of Dal bhat (a Nepali staple of rice and lentils) and a comfortable bed in a trekkers’ lodge. On the Modi Khola, as with many rivers in Nepal, we could enjoy a multiday paddling trip without any of the usual discomforts.

Paddling trips from Pokhara

From the tourist town of Pokhara, Nepal’s adventure capital, we organized many more trips. Some classic rivers—such as the Seti, Kali Gandaki and Marsyangdi—could be reached with relative ease from Pokhara using public buses, cabs and ancient footpaths. Heading to a few of the more remote rivers required patience, perseverance, some major string pulling and even the odd bribe. But fly-in trips like the Thule behri and Humla Karnali reward determined paddlers with some of the longest, best class V multidays anywhere in the world.

This article originally appeared in Rapid’s Spring 2010 issue. Subscribe to Paddling Magazine and get 25 years of digital magazine archives including our legacy titles: Rapid, Adventure Kayak and Canoeroots.

This article originally appeared in Rapid’s Spring 2010 issue. Subscribe to Paddling Magazine and get 25 years of digital magazine archives including our legacy titles: Rapid, Adventure Kayak and Canoeroots.

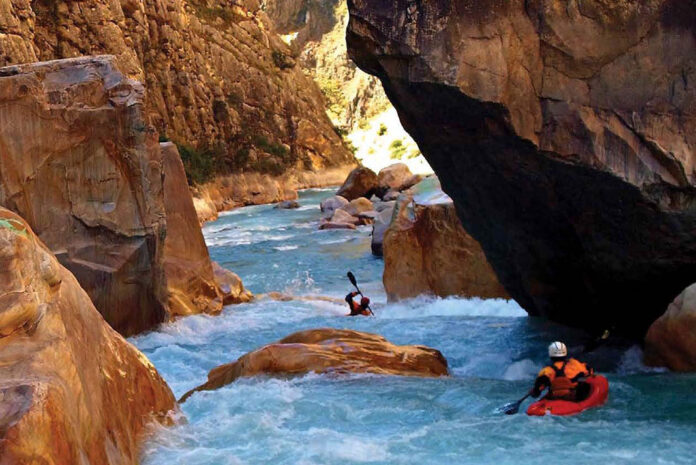

Thule Behri, day two of five. Dave Mourier and Jon Combs probe yet another drop in the deep, monsoon-flooded canyons of the remote Dolpa region. | Feature photo: Maximilian Kniewasser

This article was first published in the Spring 2010 issue of Rapid Magazine.

This article was first published in the Spring 2010 issue of Rapid Magazine.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2010 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine as part of a feature on kayak dream homes. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Spring 2010 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine as part of a feature on kayak dream homes. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2010 issue of Adventure Kayak.

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2010 issue of Adventure Kayak.