On the open Atlantic Ocean just north of Reykjavik, Iceland, the world’s most northern capital city, the shriek of a blow horn launches a dozen kayaks into a paddling frenzy. I’m by far the slowest paddler. My kayak bounces feverishly like a floating cork on monster waves. Huge cresting walls of water roll toward me and I plunge into deep troughs. I watch the landmarks on my right and barely creep forward against a frigid North Atlantic wind.

In July, 2002, I visited Iceland for the first time and had the unexpected honour of breaking into the male-dominated paddling scene in the small fishing town of Isafjordur. There, I met the singular Halldor Sveinbjornsson, Iceland’s de facto ambassador of kayaking. He encouraged me to return to Iceland later in the year to compete in the prestigious Hvammsvik marathon. He even offered to loan me a sleek Italian “Sardinia Qajaq” and began calling me the “First Lady”—because, he explained, I’d be the first woman to race the 42 kilometres from Reykjavik to Hvammsvik.

Usually I paddle only because I love to be immersed in nature. I paddle to escape my daily city life, to keep my body and mind healthy and for the excitement of exploring and travelling. I’m creatively inspired by the places I visit and by the beauty of my surroundings. Whether paddling for an hour, a day, or a week, I feel renewed, revitalized. To paddle for speed and recognition, racing 42 kilometres almost nonstop, is something com- pletely different, and suddenly I wonder what I’m doing here, and if I’ll make it.

Sea kayaking became popular in Iceland about a decade later than in North America. Only in the last five or six years has Iceland seen a dramatic increase in the number of paddlers. Halldor Sveinbjornsson has made a significant contribution to this growth. Halldor and Hvammsvik marathon race organizer Petur Gislason helped import the first mass-produced sea kayaks to Iceland by the container load from England and Italy. Now there are likely over a thousand sea kayakers with their own boats in Iceland. Not bad for an island with a total population of 287,000.

Halldor’s list of paddling achievements is almost as long as the coast of the Westfjords where he lives and paddles. This charismatic, middle-aged family man is a printer and photogra- pher, half-owner of the local print shop and newspaper in Isafjordur. When he’s not working, the level-four BCU paddler is busy promoting paddling, introducing it into the local high school curriculum, teaching rolling clinics in the local pool, and training up-and-coming marathoners like Sveinbjorn Kristjansson, a lanky 19-year-old who won the Hvammsvik race in 2001 and 2002.

THE OPPORTUNITY TO BECOME FIRST LADY

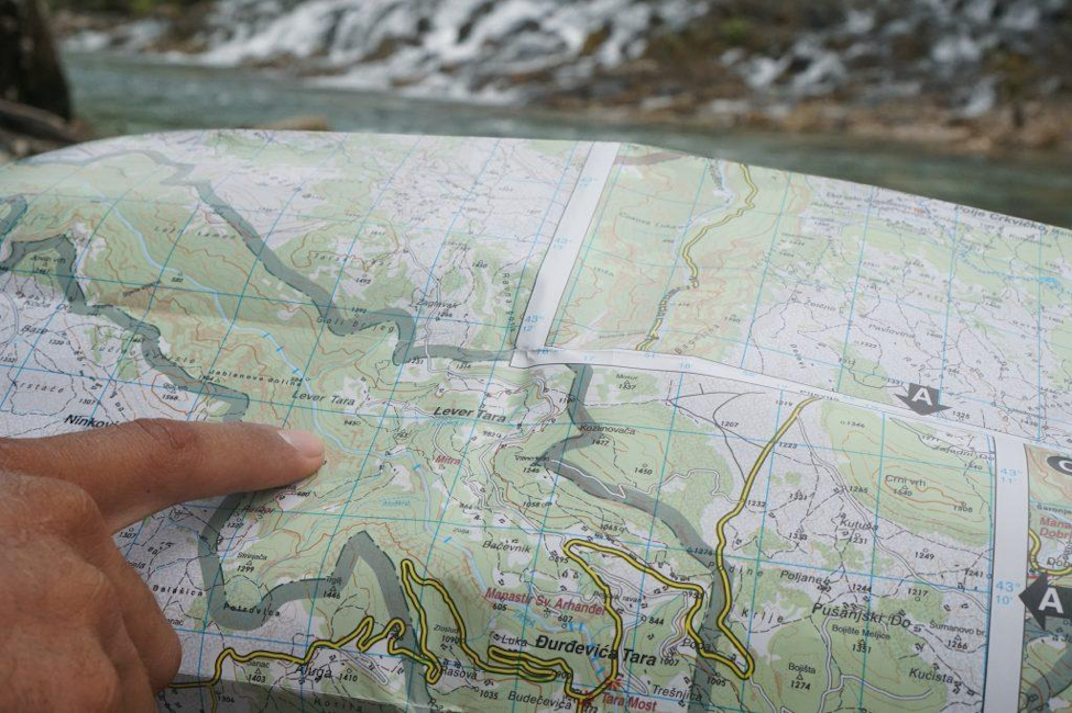

In March, 2002, I replied to an Internet invitation to join a local Icelandic paddling group on a trip to the Westfjords’ Hornstrandir coast, a wild and intricate network of fjords that comprises 10 percent of Iceland’s landmass but 50 percent of its shoreline.

Halldor, who posted the invitation, probably assumed that an American male would respond, not a determined Canadian female. The news that a woman would join their trip sent quite a buzz through the local paddling group.

Halldor, himself the 2000 Hvammsvik winner, had assembled the equivalent of Iceland’s Olympic sea kayaking team for the trip in Hornstrandir. The boys included Halldor’s racing protege Sveinbjorn Kristjansson, who became the Icelandic marathon champion in his first year of paddling; marathon contender Baldur Petursson, who instructs for “Kayakklubburinn,” the Icelandic kayak club in Reykjavik; the formidable Gummi (Gudmundar) Breiddal, a natural athlete who mountain biked across the vast interior Icelandic desert; and Sig. Petur Hilmarsson, a four-star BCU paddler who is truly as strong as a Viking. None of these men had paddled any extensive distance with a woman.

“My friends are a little bit afraid to have a woman in the group, but I’m not,” said Halldor, trying to allay my concerns about being the only woman. Halldor remarked that the group would eventually have to let women join.

It took much strong, energetic paddling to prove myself and be accepted into the group. My reward was the invitation to the Hvammsvik marathon. This was testament to Halldor’s openness to making the sport less gender-biased. I couldn’t pass up the opportunity to become “First Lady.”

About 14 kilometres into the race, we round Kjalarnes, a cliff of basalt at the mouth of a fjord called Hvalfjordur. Ahead, the fjord’s outgo- ing tide meets the incoming seas over a shallow, rocky reef, creating a taunting barricade of two-metre standing waves. Out of twelve kayakers competing, including myself, the token female, seven paddlers are ahead of me, two have quit and two have already capsized in the rough water and are flagging down the rescue Zodiac.

“I’m not going through that! No way!” I wave my paddle to the Zodiac for assistance. I flop into the boat like a hooked fish and my kayak is pulled in.

Back on the beach, I meet Halldor, who has also stopped racing. A herniated disk—a furniture-moving injury from earlier in the season—has made paddling in the rough conditions too painful for him. A sense of failure presses heavily on me. I decide I can’t drop out after coming this far, and I ask organizer Petur Gislason for permission to continue. He agrees and Halldor offers to finish the race with me.

We are in the sheltered fjord now. With the rough conditions of the open ocean behind me, my confidence soars. Halldor’s kayak slices effortlessly through the water beside me and I focus on keeping up with a steady, rhythmical cadence.

The outcome of the marathon seems less important now as it feels like a day paddle with a good friend. The afternoon sun highlights the verdant mountains and the shore’s tidy farms. Kittiwakes and gulls fly overhead within a couple of metres. An elegant male Harlequin duck swims within a metre of Halldor’s boat and, at one point, two groups of puffins fly across my bow.

When the end in Hvammsvik comes into view, a satin-smooth sheet of water spreads before us for the first time today, framed by the towering basalt columns of the shore.

Sveinbjorn, Baldur, Gummi and Petur have finished number one, two, three and four respectively, and they wait on the shore to cheer our arrival. The race officials have already removed the finish markers. We are last to drag our boats ashore, a couple of hours behind the winners with a time of 6:42. Halldor’s 2000 race record of 4:32 stands firm, and now he jokes that he can boast the fastest and the slowest record times.

AN ALMOST MARATHON

In a barn at the race’s finish in Hvammsvik, the dozen racers and their families feast on grilled lamb. Petur Gislason recognizes my “almost marathon” and presents me with a lovely gold medal bearing the image a sea kayaker.

Following the banquet, I soak away my fatigue in one of Iceland’s natural hotsprings. I’m disappointed with my lack of courage to paddle through the race’s roughest section, but satisfied with what I did accomplish.

After I return to Canada, I hear that the water conditions were worse than anything in the race’s four-year history. Considering this, Porsteinn Gudmundsson, president of Kayakklubburinn, has ruled that anyone who skipped the rough-water section will still be credited with a valid finish.

First Lady of Hvammsvik: Maybe Halldor’s nickname for me was correct after all.

Wendy Killoran is an educator and avid paddler from London, Ontario. She plans to return to Iceland this summer to further explore the Westfjords under the midnight sun.

This article first appeared in the Early Summer 2003 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Early Summer 2003 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions here.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2003 issue of Rapid Magazine. For more great boat reviews, subscribe to Rapid’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Spring 2003 issue of Rapid Magazine. For more great boat reviews, subscribe to Rapid’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Spring 2003 issue of Rapid Magazine.

This article first appeared in the Spring 2003 issue of Rapid Magazine.

This article was first published in the Spring 2003 issue of Rapid Magazine.

This article was first published in the Spring 2003 issue of Rapid Magazine.