Andrea White was in her mid-40s when she fell hard for paddling. She’d started as a recreational paddler, and as her love affair with the sport deepened, she noticed an unsettling trend. “I started hearing about incidents and fatalities in groups I paddled with, where I was two degrees of separation from people who were calling 911,” said White.

The incidents White heard about weren’t happening on difficult whitewater or rough seas. Instead, they were occurring on lakes and slow moving rivers such as the Cumberland in her city of Nashville. And the type of paddlers getting into trouble were paddlers of recreational kayaks—the group she identifies most closely with and, not coincidentally, the largest market in American paddlesports.

Inexperience is a deadly factor for rec kayakers

Recreational kayakers number more than 13 million in the United States, according to the 2021 Outdoor Foundation Participation Report. Those numbers are fueled by the accessibility of recreational kayaks, which are one of the easiest, cheapest and—one would think—safest ways to enter the sport. So why does this segment account for so many fatalities and close calls?

In a word, inexperience. Recreational kayaks are designed for and marketed to casual users, and casual users represent a disproportionate share of paddling fatalities. According to the U.S. Coast Guard’s annual Recreational Boating Statistics report, 38 percent of paddling fatalities involved participants who had less than 10 hours of paddling experience. Pull the view out further, and 78 percent of paddling fatalities involve participants with less than 100 hours experience.

Think about that for a minute. More than one-third of people who die paddling have, at best, a couple of day trips under their belts. And more than three-quarters of victims have less water time than most enthusiasts rack up in their first seasons. Those statistics are from 2021—the most recent available at press time—but they’re not outliers. The numbers have told same story for years.

While paddling disciplines such as whitewater and touring lend themselves to a culture of instructional courses and organic mentorships, the most accessible form of paddling has neither. And those who purchase whitewater boats and touring kayaks from specialty paddlesports retailers can usually count on some good advice at the point of sale, such as: where to go, what safety accessories to buy, and where to find a class or paddling group. But the majority of recreational kayaks these days are sold through box stores and sporting goods chains. For the most part, new recreational kayakers are on their own.

White and her colleagues at the ACA say inexperience goes hand-in-hand with a lack of knowledge, pointing up the need for paddling education tailored to recreational kayakers with less experience.

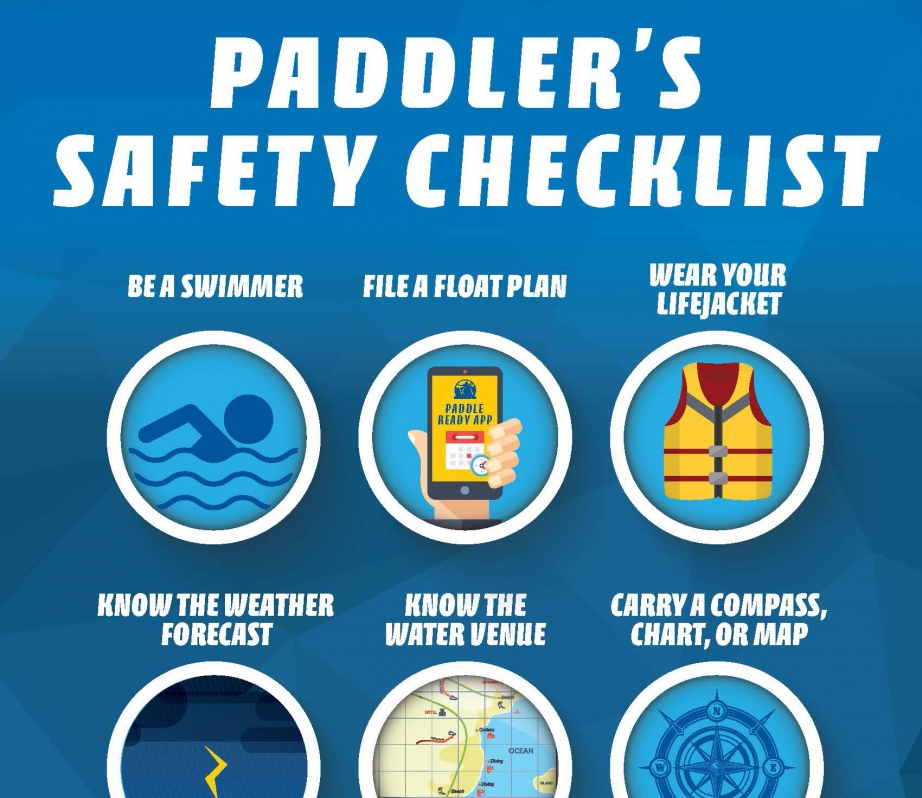

“If we look at that data and how paddlers get in trouble, it’s because they aren’t wearing a life jacket,” says ACA President Robin Pope. “It’s because they get into conditions more challenging than they’re prepared for, and because they don’t know how to get back into their boat if they have an unexpected swim.”

Turning the tide with Rescue for Rec Boaters

White has made it her mission to change this in her home state of Tennessee. As a marketing professional, she realized the paddling safety curriculum had been there all along. It just wasn’t reaching the audience who needed it most.

“I was in the community of ACA instructors who were doing this kind of training, and I could see that all we have to do is connect these two dots,” she said. “We have the training, and we have the people who want to take the training. We just aren’t offering it to them.”

White launched Rescue for Rec Boaters in 2017, hosting it through the Tennessee Scenic River Association. The two-day program is split into a lake day and a moving water day. It features entry-level instruction in paddling strokes and skills, including throw ropes, strainer avoidance and, perhaps most importantly, self-rescue. The idea is to give new paddlers in recreational kayaks the skills they need to deal with common encounters on flat and slow moving water.

The program sold out the first few years, with as many as 30 people on the waiting lists. Since then, White has relocated to Atlanta, and she brought the program with her. White credits the success of the course to its approachability—meeting recreational kayakers where they are. Her most successful recruiting tool has been social media, specifically local kayaking Facebook groups.

White’s example of finding the audience who would benefit most from safety training is a concept the entire paddling community needs to embrace. And when it comes to access and regulations, we are all legislated together.

White’s Rescue for Rec Boaters is limited to Tennessee and now Georgia. There are no plans to take her specific course national, but that is because there doesn’t have to be. The content of her course already exists in entry-level ACA courses. If instructional entities can deploy methods similar to the way White has found success, perhaps more new recreational kayakers can benefit from a safety curriculum.

Other new initiatives in paddling safety

Another tactic the ACA is taking to reach entry-level recreational paddlers is to go digital.

In Spring 2022, the ACA rolled out a free digital course in partnership with the U.S. Coast Guard. The 45-minute interactive course introduces participants to proper paddling equipment, basic skills and decision making.

“It’s not going to teach you how to run class V whitewater or go out in sea kayaks during small craft advisories,” Robin Pope explained. Instead, the program gives new boaters the baseline knowledge and skills to safely enjoy the sport. “It teaches the basic information about what safety equipment we need to acquire and what we need to wear. It teaches why it’s important to dress for cold water and always wear a life jacket.”

The idea is to make it as easy as possible for newcomers to the sport to learn how to paddle safely, Pope says. “I would love for everybody interested in paddling to come out and take a two- or three-day class, but most people don’t want to put in that type of commitment,” he says. “If we can provide a 45-minute video that’s interactive and gives them some solid instruction, then they will get on the water with increased safety.”

Recreational kayakers aren’t the only paddling segment the ACA has been working to reach.

The second largest user group in paddlesports is kayak anglers, with about 3.1 million U.S. participants and an eight percent annual growth rate, according to the Outdoor Foundation Participation Report. And, much like their recreational kayaking brethren, kayak anglers have few options for targeted paddling safety instruction. For the ACA, this has largely been a hurdle in acquiring teachers with strong skill sets in paddling and fishing.

“The ACA has many paddling instructors, but very few people paddle and fish. Fishing organizations have many people who can teach you how to catch fish, but they don’t have paddling instructors,” Pope says.

This year the ACA is changing this narrative, releasing its new curriculum cowritten by angler and paddling instructor Geoff Luckett. The first course using the new ACA Paddlesports Angler curriculum for students and instructor candidates took place over Memorial Day weekend in Tennessee.

Rescue training has a ripple effect

Getting every paddler to take a safety course isn’t a realistic goal, but White says the structured courses don’t have to do all the work. Part of what makes her Rescue for Rec Boaters course effective is the ripple effect, she says. Every course sends a miniature armada of safety conscious paddlers back into the recreational kayaking community.

“I tell ’em on the rivers, ‘You are now in the top 10 percent, most knowledgeable, most-trained people out there. You are now the ambassador of these skills to everybody you paddle with and interact with,’” White said.

“You give people a role to play as part of their community, and they do what all river people do. They propagate knowledge.”

White coaches a paddler at a recent Rescue for Rec Boaters training. | Feature photo: Bonnie Murphy