There’s no reason you can’t get on the water this spring as soon as the ice goes out. Paddling in the cold is safe and fun as long as we remember what our mothers taught us—dress for the weather, sure, but also for the water.

As a general guide, follow the 100-degree rule: dress for cold water any time the water temperature and air temperature add up to less than 100 degrees F (37 C). Also take into account other factors like your experience, the distance you are from shore, water conditions, and whether you’re solo or in a group. If in doubt, consider the water temperature, assume you’ll go over and dress for immersion.

The point is to be safe and also comfortable, and with the right clothing, you can have both.

Your Body in Cold Water

When dressing for cold water—anything below about 15 C (60 F)—it helps to understand what happens physiologically when you are immersed. There are really two dangers to prepare for: the shock of initial immersion, and the cooling effect of prolonged immersion.

This is a key point made by the world’s leading authority on the subject, Gordon Giesbrecht , director of the University of Manitoba’s Laboratory for Exercise and Environmental Medicine. Nicknamed Professor Popsicle, Giesbrecht has voluntarily lowered his body temperature below the hypothermia threshold (35 C; 95 F) over three-dozen times for the good of science.

Contrary to what you might think, Giesbrecht’s experiences show that it takes some time to become incapacitated by hypothermia in cold water. His 1–10–1 principle explains what happens to the uninsulated body in cold water: In the first minute of immersion you gasp and hyperventilate; the danger in this stage is that you’ll panic and inhale water.

If you can remain calm, control your breathing, begin to tread water or hold onto your boat, the initial shock will subside and you’ll have about 10 minutes of good muscle function to call for help, climb back into your boat or head for shore. Then the cold starts to take effect but you’ll remain conscious for about one hour.

Dressing properly can prolong every stage of this process: reduce the shock of cold water immersion; increase the time you have to rescue yourself; and increase your survival time if you have to wait for rescue.

Wetsuits

Wetsuits are snug-fitting garments made of neoprene rubber that let in only a small amount of water, which is then heated by the body to provide a protective layer of warmth. Paddling wetsuits are generally made of 3-millimetre neoprene. In warm air temperatures, it can be more comfortable to wear a wetsuit all day than a drysuit, especially a shortie or farmer john– style suit that covers just the core. Wetsuits offer the versatility of adding a splash layer such as a paddling jacket for protection from wind, spray and rain. Wetsuits are less expensive, longer lasting and easier to maintain than a drysuit (there’s nothing worse then blowing a gasket or getting a pinhole in your drysuit).

Drysuits

A drysuit creates an actual barrier between you and the cold water. Drysuits are made of completely waterproof material complete with latex seals on the wrists, ankles and neck. The best suits use waterproof-breathable materials like Gore-Tex to reduce condensation, and include essential features like built-in socks and relief zippers.

By creating a wall between you and the water, a drysuit eliminates the “gasp” effect when you hit the water. How long you can last once immersed is determined largely by what you wear underneath. With a drysuit you have the ability to regulate the warmth by adding or subtracting under layers. The best way to refine the layering system is to jump in the water and see how it feels.

You have a choice between a one-piece drysuit or a two-piece drysuit, comprised of a jacket and pants or bibs. A one piece is the norm, because it’s the most watertight. There are advantages to a two-piece, however. First, with the top and bottom being separate, you’re able to get more movement in the groin and shoulders, and better options for fit since the top and bottom can be purchased in different sizes. Also, for the upper layer you can wear either a full drytop or another type of jacket such as a hooded anorak—which is not as watertight but more versatile and comfortable. With the latter, since there is no rubber neck gasket which some believe is the Achilles heel of the full drysuit, you’re spared those embarrassing neck hickies. In warm, calm conditions when you’re not worried about flipping, you can just wear the bottoms to keep your lower half dry.

Under Layers

The warmth of a drysuit comes from the layers you wear underneath: a base layer and an insulating layer. For the base layer, wear a synthetic fabric such as polyester or polypropylene that wicks moister away from the skin. The insulating layer can be synthetic such as the Immersion Research Thickskin Union Suit (immersionresearch.com; $95 US), merino wool, or a synthetic-merino blend such as Woolpower, which is woven with terrycloth loops to hold a layer of air next to the skin.

Merino wool is pricier than synthetic but has several advantages: it doesn’t feel prickly like traditional wool; it absorbs up to 30 per cent of its weight in water while still providing insulation; it is a renewable, natural product;

it doesn’t retain odours; and for après paddle fireside safety, it’s flame resistant.

Splash Layers

When the water temperature is relatively warm but the air temperature is cold, consider putting on a paddling jacket and pants. These splashproof items are perfect for wearing over wetsuits. A hooded paddling jacket also saves weight by doubling as a raincoat.

Hats, Mitts and Booties

Extremities get the final word. Neoprene booties and gloves, with additional neoprene bootie and glove liners for extra cold conditions, work wonderfully. For the coldest conditions, use pogies (mitts that Velcro to a paddle shaft) and wear thin neoprene gloves underneath.

For the head, a balaclava-style paddling hood provides the ultimate warmth, or you can wear a neoprene or fuzzy rubber skull cap (helmet liner) or a plain old wool tuque.

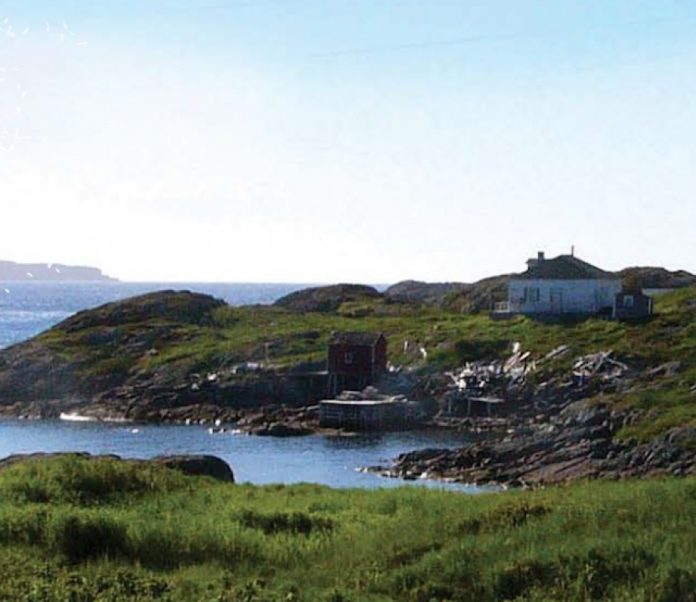

This article first appeared in the Spring 2010 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine as part of a feature on kayak dream homes. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions

This article first appeared in the Spring 2010 issue of Adventure Kayak Magazine as part of a feature on kayak dream homes. For more great content, subscribe to Adventure Kayak’s print and digital editions

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2010 issue of Adventure Kayak.

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2010 issue of Adventure Kayak.